Eventually, our locomotive rested at the Samarkand rail station:

After hotel check-in and lunch, our new guide and driver began our tour. First stop was the mausoleum of Amir Temur:

Inside, we studied the visage of this man named Temur in an artist’s rendition:

Nevertheless, Temur shook the world of his time with his conquests. A brilliant strategist, his boundless ambition drove him to plunder and sack cities throughout central and western Asia, from as far south as Delhi to as far north as Moscow. Samarkand, his imperial capital, grew spectacularly wealthy from the spoils of war and the work of his slave-artisans. Temur went beyond simply creating an empire, for he was sadistic, cruel, ferocious and barbaric. His horrifying exploits left an estimated 17 million people dead during his 40-year trail of destruction!

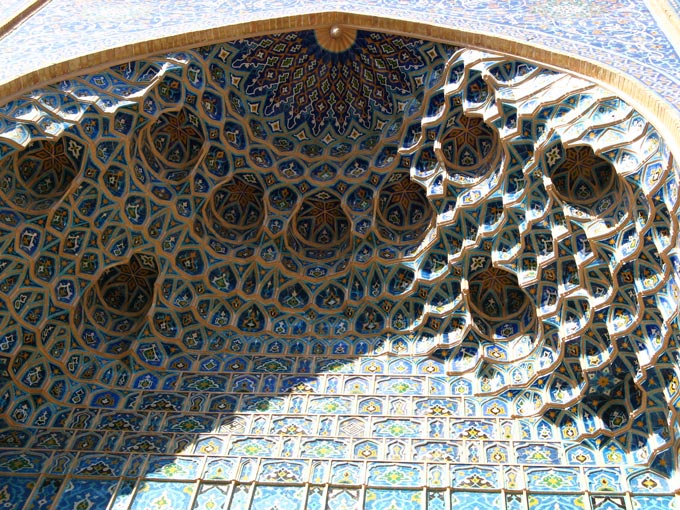

Standing inside the mausoleum and checking out the interior from top to bottom, you would see richly decorated surfaces, enveloping the crypts below:

Before taking leave of this remarkable mausoleum, we walked around to the back for a closer view of its fluted dome:

The mausoleum, it turned out, was just a warm-up. The main attraction in Samarkand was next on our agenda. As far as man-made structures are concerned, this attraction presents one of the most spectacular scenes anywhere:

By good fortune, we were able to stand at this stunning viewpoint not just in the afternoon but again the next morning. The sun brightened parts that were in total shade the day before ...

Considering the three structures in their chronological order, the one on the left is called the Ulugbek Madrassa after the ruler who ordered it built. Fittingly so, because his love for mathematics, astronomy, medicine and theology drove him towards all things educational.

Not surprisingly, the splendid building we see today, nearly six hundred years old, has had substantial help in surviving to this age and looking this good. The photo below, taken in the 1920s, speaks volumes as to its then dilapitated state:

Similar photos of all three madrassas depict leaning towers, domes with gaping holes, crumbling facades ravaged by time, wind and centuries of neglect. In the 1920s, the first attempts at stabilization were made, namely, straightening leaning towers before they fell. Beginning in the mid-1960s, restoration accelerated and continues today. Much of the effort was funded and directed by the Soviet Union prior to 1991. The motivation must have been to create more income from tourism, a very long-range goal. The impressive nature of these monuments was recognizable even in their ruined state.

More than 200 years after the Ulugbek Madrassa was built, another was constructed facing it. The Shir Dor Madrassa was a match in size and beauty:

The next two photos really capture the stupendous size of this madrassa:

We were able to enter a room under the dome on the building’s left side to admire its ornamentation:

Below are two photos of this madrassa in the 1920s. The animal figures on the facade are barely discernible:

The middle madrassa, Tillya-Kari, was completed a scant 24 years after the second:

Today, none of these buildings are used for their original purpose. If there is a mosque still open and functioning, we did not see it. Many of the former student cells are now souvenir shops. Regardless, the restored buildings are vivid reminders that people in central Asia were capable of erecting enormous and beautiful structures, even centuries ago.

Before leaving the Registan, we must comment on the “street sweepers”:

After the Registan, anything would be anti-climactic. However, we had a fascinating spot to visit next that really peaked my interest, the ruins of Ulugbek’s astronomical observatory. To really appreciate it, a bit of background on this Mirzo Ulugbek would help.

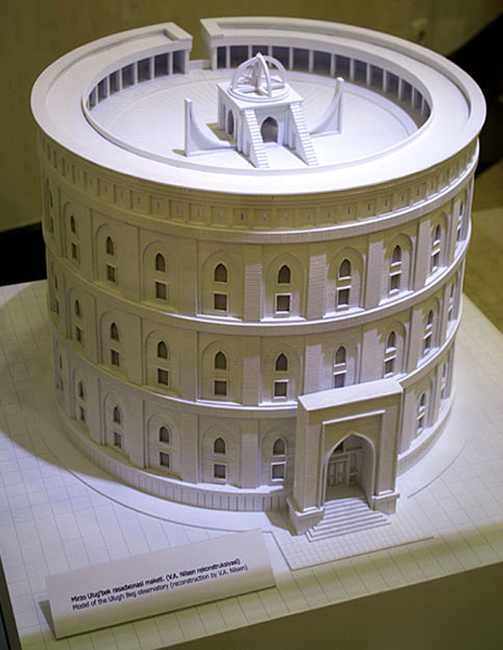

After completion of his madrassa in Samarkand (and others elsewhere), Ulugbek ordered an astronomical observatory built. Finished in 1429, it contained the largest sextant in the East, a circular arc with a radius of 118 ft, spanning 90 degrees. Most of it was below ground but the upper end reached to the top of his three-story observatory. Its scale ensured unparalleled accuracy and made Samarkand the stargazing capital of the 15th century. It was his crowning achievement and his path to disaster. The model below is believed to represent the observatory:

With his circle of experts, Ulugbek plotted the coordinates of 1,018 stars, devised rules for predicting eclipses, measured the sidereal year to within one minute of modern calculations and determined the Earth’s axial tilt as 23.52 degrees (which remained the most accurate measurement for hundreds of years). All of this was done without optical instruments. In mathematics, he wrote accurate trigonometric tables of sine and tangent values correct to at least eight decimal places.

Sadly, Ulugbek’s scientific expertise was not matched by his skills in governance. In fact, he spent as little time as possible in public affairs, preferring instead his beloved astronomy. He made several tactical errors, militarily and politically, antagonized the clergy by implying that science would outlast religion and gained the adamant opposition of radical clerics. He was seen as a weak and ineffective ruler (which he probably was). On a pilgrimage to Mecca in 1449 to make amends for his “errors,” he was assassinated on the order of a sharia court.

In the immediate aftermath, all of his observatory above ground was destroyed. All evidence of its location was obliterated and the population forbidden to mention his name.

The whereabouts of the former observatory lay wrapped in mystery for centuries. It took a persistent, fully-committed, Russian archaeologist named Vyatkin years of painstaking research before he found it in 1908. Today, the hill in Samarkand on which the observatory stood is attractively landscaped, there is a small observatory museum and a statue of Ulugbek. The only relic of the observatory that remains is the underground portion of the giant sextant:

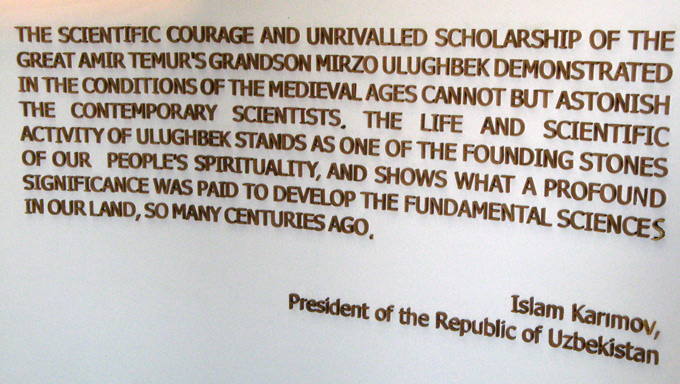

All of Ulugbek’s work was not lost, however, despite the extreme measures taken by his opponents. His closest colleague managed to escape Samarkand with Ulugbek’s star catalogue and bring it to Europe where, after translation, it created a sensation. Consequently, Ulugbek is now well-appreciated in his homeland and in the circles of astronomical history, ranking on an equal footing with Copernicus, Galileo and Ptolemy. In the museum is this tribute by the current President of Uzbekistan:

Our last stop with our guide was a necropolis named Shah-I-Zinda, difficult to appreciate with only this one late-afternoon shot: