Bukhara

-

The Sharq, our train from Samarkand, is called a fast train but its top speed is reputedly just 65 mph. The three hour journey was comfortable, though, once we figured out how to let in fresh air. We had a three-person compartment all to ourselves:

Prior to arrival, we did some research. Bukhara is a very old city. Its historical records go back more than 2,500 years. With all its ancient monuments, it is no surprise there is a restoration program akin to Samarkand’s. Building restorations begun in the 1960s under the USSR have continued since independence.

Most of the upgraded mosques, madrassas, mausoleums, and such are no longer used as originally intended; so, a new function is sought for each. Some madrassas have been turned into craft centers, studios, and galleries. One has become a restoration institute where future restorers are trained. A caravanserai is now a silk and cloth warehouse, and trading domes function as active marketplaces.

Moreover, mediocre buildings of the 1950s have been removed, utilities upgraded, and streets paved. Old Bukhara --- apparently, a derelict slum not so long ago --- is now a viable, prosperous city and a tourist magnet.

At the rail station, as before, we met a new guide and driver and were taken as close to our hotel as possible. From there, we went on foot through well-stocked marketplaces, where we had a sneak preview of goodies we might acquire later.

Our hotel was well-located in the old town, near sights we would soon visit. For example, this photo, taken from the shaded hotel patio, shows the Kalyan Minaret and (the side of) the Miri-Arab Madrassa, just outside the hotel walls:

After settling in, we went out to explore them.

The Kalyan Minaret is considered a symbol of Bukhara. 155 feet high, it has been standing on this spot since the year 919:

Tall as it is, the minaret has served multiple functions. First and foremost, it has called Muslims to prayer at the great mosque nearby. In times of war, it has served as a look-out tower to detect approaching armies. As a lighthouse in times of peace, it has helped guide caravans through desert wastelands to the city. Its most nefarious use has been for execution, the hapless criminal being tossed from the top to certain oblivion below. That practice ended only in the late 1800s.

Below is the same view Genghis Khan had in 1219:

So struck with wonder was he that he spared the minaret from the city-wide destruction that followed.

This is the front of the Miri-Arab Madrassa, the side of which we could see from our hotel:

It was built in the 1530s and named after its founder. On the Internet, I came upon this interesting photo of the madrassa from a vantage point I could not match:

In the photo below, the madrassa is to the left, out of camera range. Facing it is the Kalyan Mosque. Note that the entrance to the minaret’s inner staircase is reachable only from the mosque. We observed a similar arrangement for the entrance to the Burana Tower in Kyrgyzstan, where the mosque no longer survives.

The Kalyan Mosque is called the “Great Mosque” in deference to its capacity. In 1514 when it was built, all the men in the city were expected to attend Friday prayers here each week. Consequently, it was constructed with an open-air capacity of 10-12,000 men. The Internet shot below looks back toward the entrance with the minaret and the madrassa outside.

Wandering about town, we saw as much diversity in madrassa ornamentation as in Samarkand. For example, this one has an intricate stalactite work unlike others:

Constructed in the 1600s, it bears the name of its founder, Abdulaziz Khan. It now serves as the Museum of Wood Carving Art.

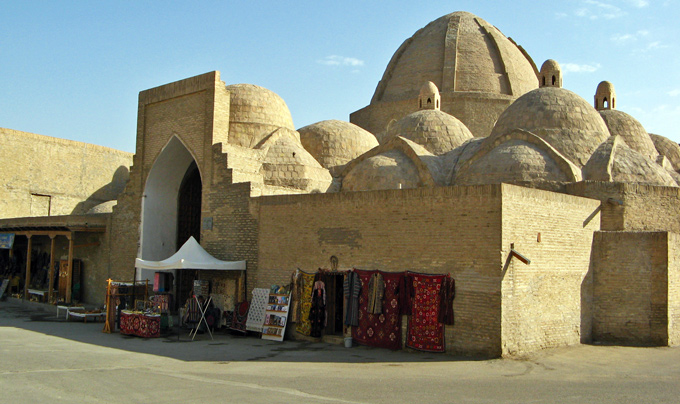

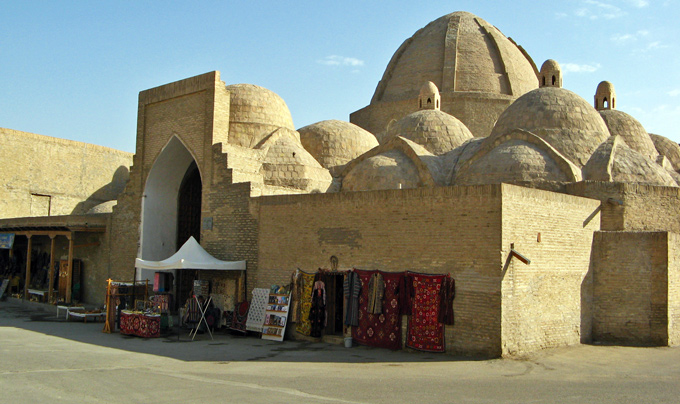

We entered several trading domes, which are essentially covered bazaars:

Originally built for Silk Road trade, a few still survive in Bukhara. Looking into such a marketplace without entering, you would see arched passageways big enough for a laden pack camel:

Only by entering, though, would you see everything that is being sold. Some items, we thought, were downright remarkable:

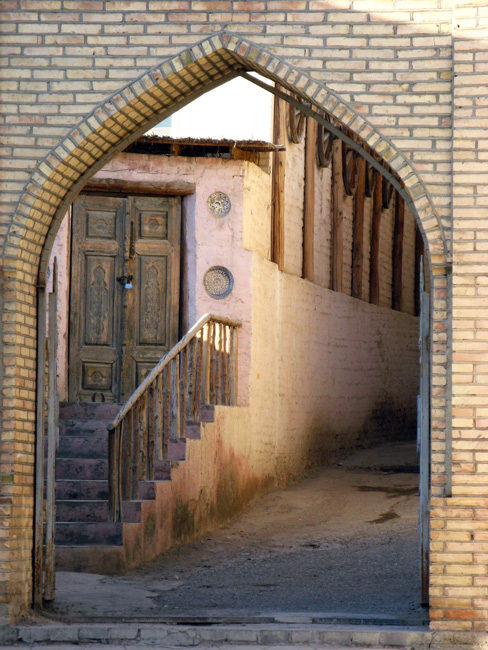

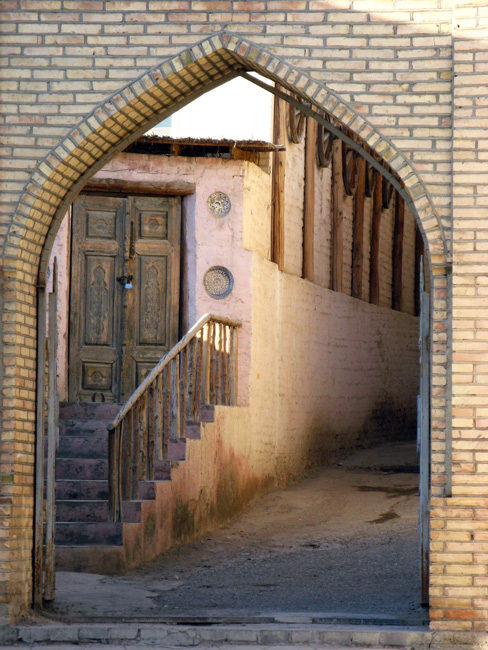

The view through this archway was sufficiently remarkable for me, resembling a framed painting ...

... but, perhaps, it still needs a bit of photoshopping.

THAT is not what the Ark Citadel needs. It would be hard to dream up more peculiar defensive walls than this:

Photographically, I could not get enough of it:

Looks can be deceiving, however. The walls ARE massive and may appear invincible --- barring cannon fire --- but, in fact, over the centuries they have proved to be unstable, eroding and crumbling without provocation. The reason is that inside the mud brick veneer is an earthen mound, thought to be supplemented with building rubble. Even today, the walls need ongoing upkeep as they are prone to collapse.

Historical records from the 7th century are the first indication of a fortress on this site. That fortress repeatedly collapsed and was repeatedly rebuilt until the Mongols came along in 1219. They flattened it. The Ark took its present shape in the 16th century, gradually developing into a mini-city of 3000 inhabitants, complete with palace, harem, treasury, mosque, mint, dungeon, slave quarters, --- you name it.

During the Bolshevik Revolution in 1920, 80% of the complex was destroyed by fire. The leader of the Bolsheviks, that rascal Mikhail Frunze whom we “met” in Bishkek, usually gets the blame. The Ark has never fully recovered from that disaster.

So, why is it called the “Ark”? The only explanation I have seen suggests that, in Persian, “Ark” means fortress or citadel. ... If so, “Ark Citadel” is a bit redundant.

Eventually, we reached the main entrance of the Ark, which early on had been equipped with a drawbridge:

A few buildings inside are open for touring, though nothing spectacular is to be seen. Nevertheless, we ascended the ramp to investigate.

The best preserved part is the Court Mosque, now a museum:

Its walls and its ceiling are colorfully restored:

In another museum the most intriguing item I could spot was a self-contained fire extinguisher, made in the USA. Its “Operating Insturction” (sic) was provided in English --- sort of.

We had our last view of the Ark from across the street ...

... as we headed for the “Mosque of 40 Columns”:

“But, there are ONLY 20!” I hear you protest. ... Ah, but you failed to count the reflections!

The minaret for this mosque is just a baby and almost cute:

Tall and spindly, the columns on this mosque are graceful to the point of making you wonder how they hold the roof up:

Walking on, we paused at this austere building with its unusual conical dome:

Inside, a spring flows with water believed to have healing powers. This is the legendary “Spring of Job,” initiated by the Prophet Job during a prolonged drought. The building was created during Temur’s reign and is also a mausoleum.

A little farther on is another mausoleum, which features a hemispherical dome resting on a cube:

Built in the 9th or 10th century by the Samani dynasty as a family crypt, this monument was a novel idea at the time. It is considered to be the first Muslim mausoleum in central Asia.

How did it survive Genghis Khan? The story we got was that sandstorms buried the mausoleum before the Mongols arrived. Hidden from sight, it was saved from destruction!

Down a labyrinth of narrow and winding streets in the old town is my favorite Bukhara monument:

More Indian, perhaps, than Uzbek, it is both charming and picturesque. Its name is the Chor-Minor Madrassa and it was completed in 1807, financed by a rich merchant. He is rumored to have had four daughters and I can believe it. We noted that each minaret is different. The Chor-Minor, we’re told, means “four minarets.” It looks just as good from all sides:

Part of its attraction may lie in the fact that it is neither ostentatious nor perched on a hill. Instead, it nestles quietly in a recessed courtyard with a pond and shade nearby.

Our guide arranged lunch for us in a private home. When we arrived, the meal was already cooking on the patio:

Our dining area was lovingly decorated from floor to ceiling:

Our meal was ... what else? ... plov, the national dish of Uzbekistan:

We found it tasty though on the heavy side; it is more commonly a mid-day meal rather than an evening meal as it is quite filling.

With our Bukhara tour winding down, we learned a bit about this comical fellow on mule back:

His name (though spelled many ways) is Khodja Nasraddin. Supposedly, he was a real person who lived in 13th century Turkey. Today, he is regarded as a populist philosopher and wise man, remembered for his funny stories and anecdotes. He appears in thousands of stories, sometimes witty, sometimes wise, but often a fool or the butt of a joke. He personifies a quick-witted, warm-hearted man.

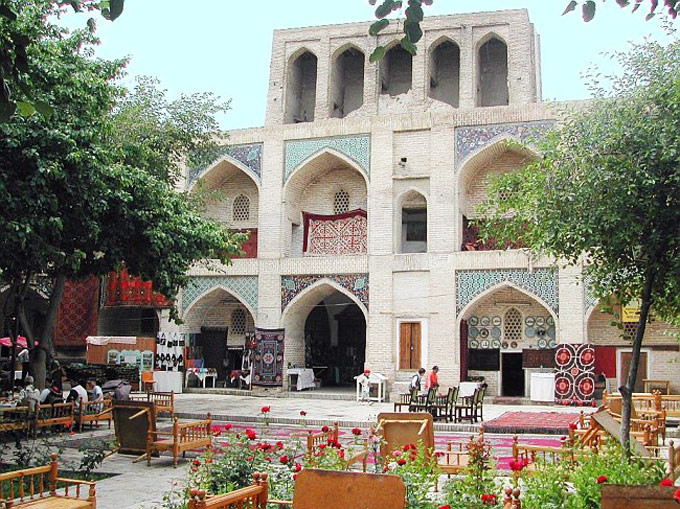

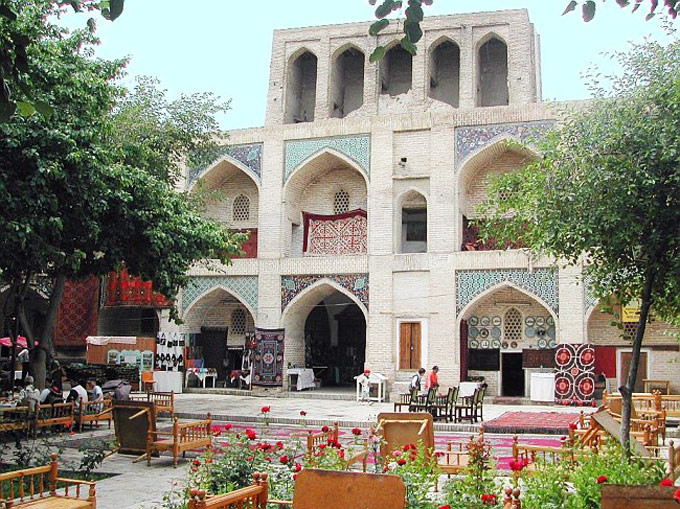

To wrap up our visit, we entered this brightly decorated building behind Nasraddin, which dates from the 1630s:

Built as a caravanserai, it was mistakenly decreed a “madrassa” by an Islamic clergyman and hastily changed to just that by the owner. The atypical frieze above the entry dates from that period. It depicts a sun and two fantastic birds, each carrying a white deer in its talons.

I did not take a photo of the inner courtyard but found this one on the Internet:

Around the perimeter are craft shops and sellers. The central portion is set up for an evening folklore show, a performance we missed as we were back in Tashkent by dinner time. Bye-bye, Bukhara!